One evening in 1958, the pianist Dave Brubeck and his quartet gathered in the home of a jazz-loving industrialist on Mumbai’s Malabar Hill to chat with a group of Indian musicians led by the sitar maestro Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan. Then they picked up their instruments and put their new knowledge to work. The jam session with Khan, the American pianist said later, changed the way he approached his art. “His influence made me play in a different way,” Brubeck told Jazz Journal International. “Although Hindu scales, melodies and harmonies are different, we understood each other…The folk origins of music aren’t far apart anywhere in the world.”

More than 50 years after Brubeck’s India tour, fans in Rajkot and Chennai, Hyderabad and Calcutta, still have warm memories of the quartet’s concerts. But in addition to the magical music, they still smile at recollections of Brubeck, the saxophone player Paul Desmond, drummer Joe Morello and bassist Eugene Wright ambling through town, sitting in with local bands and having long discussions with Indian fans. That’s exactly what the US State Department hoped to achieve when it started putting jazz bands on the road in 1956.

In August that year, as the Cold War was growing icier, the US Congress sanctioned funds for the President’s Special International Program, an initiative that aimed to showcase the superiority of the American way of life to the world – especially the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa. Jazz quickly became the programme’s centrepiece. Jazz, after all, was the only home-grown art form the US could boast of. Just as important, it was an African-American art form. At a time when many people in the newly independent world were appalled by the segregation faced by African-Americans in the US South, foregrounding jazz gave Washington the chance to pretend that this discrimination wasn’t as harsh as some people imagined it to be.

In August that year, as the Cold War was growing icier, the US Congress sanctioned funds for the President’s Special International Program, an initiative that aimed to showcase the superiority of the American way of life to the world – especially the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa. Jazz quickly became the programme’s centrepiece. Jazz, after all, was the only home-grown art form the US could boast of. Just as important, it was an African-American art form. At a time when many people in the newly independent world were appalled by the segregation faced by African-Americans in the US South, foregrounding jazz gave Washington the chance to pretend that this discrimination wasn’t as harsh as some people imagined it to be.

Interviewed about his India trip on the weekend of his ninetieth birthday last year, Brubeck understandably was hazy on specific details. But he had one strong memory. The piano he was supposed to use for his concerts in Mumbai had got warped in the tropical heat, so he went to a music store and tried out several instruments. He eventually found a Bosendorfer that was to his liking. Suddenly, “several porters came in, put the piano on their heads and carried it through the streets” to the venue. They had to march in perfect rhythm because a misstep would cause the instrument to slide to one side and possibly crash to the ground.

The substitute instrument didn’t cramp his style. The Times of India’s music critic was among those who could not contain his appreciation for Brubeck’s concert at the Eros Theatre on April 4, 1958. “Pianist most outstanding,” glowed the newspaper’s review, advising, “If you have not yet heard this fantastic group, pinch your neighbour’s ticket if necessary but go and hear it. If you have already heard it, go again. It has the inestimable gift of being able to take the starch out of music snobs – and there are so many of us in this great city.”

Over the next few years, other jazz greats followed Brubeck to India. In 1959, the impeccably-coiffed Dixieland trombone player Jack Teagarden was dispatched to the frontlines of the battle for hearts and minds. In 1960, Mumbai welcomed the trumpet player Herbie “Red” Nichols. Nichols had been recording prolifically since the 1920s, but he’d shot to world-wide fame only in 1959 with the release of The Five Pennies, a semi-biographical film starring Danny Kaye.

In 1963, the Americans deployed one of the most charming musicians in their arsenal, the dashing Edward Kenney Ellington. Many of Ellington’s sidemen were stars in their own right, so it was no surprise that they were mobbed by autograph seekers when they arrived in Mumbai.

Ellington was installed in a split-level honeymoon suite at the Taj Mahal Hotel facing the Arabian Sea. Shortly after he checked in, he rang for room service and asked the waiter what food was available. “I begin by reciting my favourites and get all the way down to chicken but he responds to every item by shaking his head side to side,” Ellington wrote in his memoirs. “Although I am right here on the sea, he shakes his head again when I mention fish. Not knowing any better, I wind up eating lamb curry for four days, after which I discover that shaking the head from side to side means ‘Yes.’” As the 64-year-old Duke realised, cultural exchange was a tricky business.

Though the jazz tours were warming the hearts of audiences around the world, at home in America, jazz musicians were becoming increasingly disgruntled with the way the State Department was organising these jamborees. For one thing, the diplomats they ran into in places like Iraq and Pakistan and Indonesia were often old-school racists and treated the visiting African-American stars with condescension, if not outright contempt. Besides, by the beginning of the 1960s, the battle for civil rights in the US had intensified immensely and many musicians, both African-American and white, were frustrated that their government simply wasn’t acting swiftly enough to fix the problem. Some of them began to feel that it was hypocritical for the State Department to send African-Americans around the world as an example of American democracy in action when they weren’t allowed voting rights in the US South.

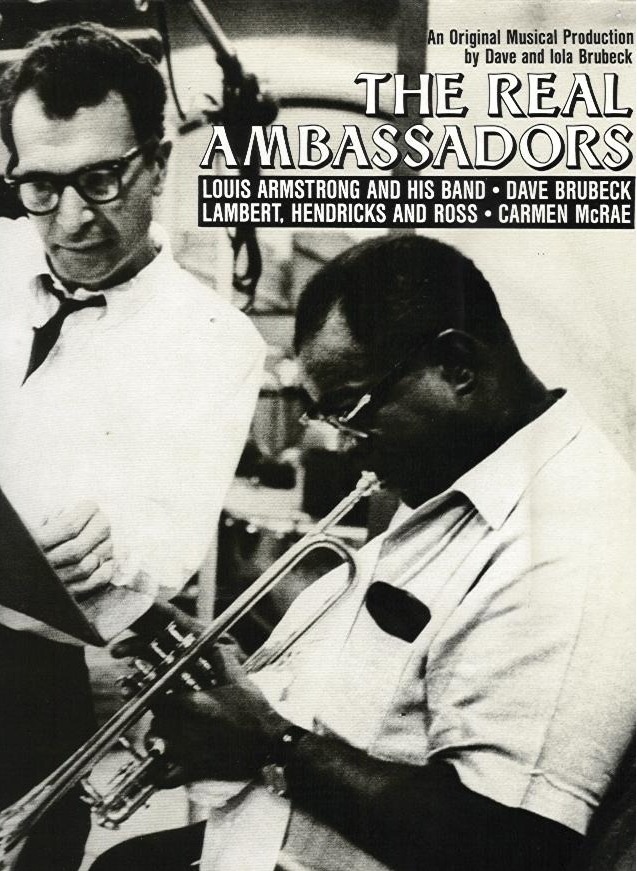

In 1962, Dave Brubeck and his wife Iola got together with Louis Armstrong and other jazz stars to produce a jazz opera pointing out these paradoxes. It was called The Real Ambassadors and was a witty, stinging indictment of the Cold War jazz project. It was performed at the Monterey jazz festival in 1962 and went down very well with the crowds. Plans were made to take it to Broadway, but that didn’t happen. In the racially charged environment in 1960s America, The Real Ambassadors was considered too incendiary.

In 1962, Dave Brubeck and his wife Iola got together with Louis Armstrong and other jazz stars to produce a jazz opera pointing out these paradoxes. It was called The Real Ambassadors and was a witty, stinging indictment of the Cold War jazz project. It was performed at the Monterey jazz festival in 1962 and went down very well with the crowds. Plans were made to take it to Broadway, but that didn’t happen. In the racially charged environment in 1960s America, The Real Ambassadors was considered too incendiary.

As the 1960s progressed, the Cold War tours continued, but jazz became increasingly less prominent in them. After all, musical tastes around the world were changing and the US State Department wanted to reflect this – so R and B became a priority, as also gospel performers. Besides, in 1967, the American magazine Ramparts revealed what many had long suspected: that the CIA was indeed funding cultural projects around the world. This made some Indians wary of the jazz tours. The State Department tours continued until the late 1970s, but in India, they had reached their high point with the Brubeck, Ellington and Armstrong performances.

Here’s a song from The Real Ambassadors.

[A shorter version of this piece first appear on the New York Times’ India Ink blog.]

2 comments

I am garndson of Mr N. D Koli. Please give me more information If you have Because I also learn Pakhawaj

I was at that concert on April 4, 1958 and all the more memorable since it was my birthday. However, we waited half an hour to get his autograph outside the Eros Theatre after the concert but were told he was not seeing people. In the early 1990’s I went to Montreal to watch him perform and we were willingly led in to meet Brubeck, who was with his wife, and another gentleman whom I don’t remember.

He was thrilled at the old album cover I present for his autograph and said: Oh look at this old recording!! I told him about waiting to see him personally in Mumbai but were told he was not entertaining visitors, he recoiled with shock in voice and demeanour: Oh!! And looked with questioning eyes at his friend.

Yes, I am forever a Brubeck fan from the age of 19.