In December 1905, Giovanni Scrinzi, an Italian musician living in Bombay, wrote a letter to The Times of India with a bold suggestion. The time was right, he argued, for the city to establish a permanent orchestra. Bombay was home to “a not inconsiderable class of cultured people of all communities” who would appreciate such a venture, he declared. Already, the city’s elite had supported a school of art, Elphinstone College and a museum. But music – “the most ideal and perhaps refining of all arts” – was yet to receive the encouragement it deserved. “Is it not fair that an appeal should be made on its behalf?” he concluded.

It took 15 years Scrinzi’s idea to become a reality. But this month, as the Symphony Orchestra of India returns to the National Centre for the Performing Arts for its eleventh season, I spent some time in the archives marvelling at just how long Bombay’s association with Western classical music reaches back.

It’s a history that began in the mid-sixteenth century, when the Portuguese established themselves in Bassein, bringing with their musical tastes with them. By the seventeenth century, Indians were performing Western music too. That is established from the accounts a young British doctor named John Fryer left of a visit he made in 1675 to the Jesuit-run College of St Anne in Bandra (which stood near the railway station, in the lot now occupied by the bus depot). He described the College as being “thwacked full of young blacks singing vespers”. On a second visit shortly after, Jesuit priests entertained Fryer at a stately banquet with fine fruit and wine, “diverting us with instrumental and vocal music”.

When Bombay grew into a commercial town under British rule, amateur performances by European colonels and their wives became commonplace. Occasionally, tours by professional musicians from Europe enlivened the scene: an Italian opera company was imported as early as 1865. As the city grew in prosperity and confidence, debates began about the viability of establishing a permanent orchestra to supplement the marching bands that had been raised by the Governor, military units and the railways.

Shortly after Scrinzi’s letter to the Times, the discussion was joined by a correspondent using the name Viola. He lauded the idea, but was quick to point out the pitfalls. Bombay, he said, simply didn’t have enough talent to support a permanent orchestra. One option, he said, could be to attract talented European musicians to Bombay, with the offer of fulltime salaries and pensions, though he suspected that they would soon get discontented with the city’s “lack of musical life”.

But another thought presented itself: “Take the material at hand here, viz the Goanese musician. Take these fellows, train them on the best European methods of teaching, drill them at their work and I am confident that you have the best material for the formation of a Municipal orchestra in Bombay.” It wasn’t as if parallels did not exist, said Viola: “Daily we see here in Bombay before our eyes what British training methods have done for Native soldiers so why not on different lines for these Musicians?”

It took until 1922 for the vision to become a reality. When the Bombay Symphony and Chamber Orchestra gave its first concert at Excelsior Theatre under the baton of Edward Behr, a German who headed the Governor’s band, it was largely staffed by the “Goanese musicians” whose talents “Viola” had identified 15 years before. These musicians had benefited from the music education system established by the Portuguese who had ruled their home territory since 1510. Though a news report on the Bombay Symphony and Chamber Orchestra’s fifth anniversary said that an average of 500 people attended its weekly Thursday concerts at Cawasji Jehangir Hall, the revenues weren’t sufficient to keep the outfit alive. The deficit, as it had been since the outfit was started, was being filled by the Parsi merchant JB Petit.

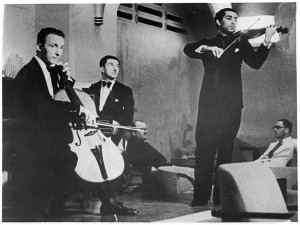

But the orchestra collapsed in 1928, after Petit found himself unable to renew his support. The ensemble in the photo at the top of the page is the Taj Light Symphony Orchestra, depicted at their inaugural performance on January 25, 1935. On that day, it played works by Elgar, Debussy and Ravel, among others. Though the Belgian conductor Jules Craen is the most prominent figure in that photo, if you look closely, you can see another important Bombay figure to the left. The violinist Mehli Mehta sits confidently in the front row of the cluster behind Craen, his bow held lower than those of his colleagues.

Though Mehli Mehta is now mainly remembered as the father of the legendary conductor Zubin Mehta, he was among the mainstays of the city’s Western classical music scene for more than a decade, until he moved to the US in 1945. In 1940, he made the first disc of Western classical music recorded in India that I own. (He wasn’t the first Indian to record Western classical music: I’ve seen references to a record made for HMV even earlier by a musician named JP da Costa – though I’ve never heard that disc, which the Bombay Chronicle described as “unpretentious and modest”.)

Though Mehli Mehta is now mainly remembered as the father of the legendary conductor Zubin Mehta, he was among the mainstays of the city’s Western classical music scene for more than a decade, until he moved to the US in 1945. In 1940, he made the first disc of Western classical music recorded in India that I own. (He wasn’t the first Indian to record Western classical music: I’ve seen references to a record made for HMV even earlier by a musician named JP da Costa – though I’ve never heard that disc, which the Bombay Chronicle described as “unpretentious and modest”.)

Since then, Bombay has been home to many orchestras of varying longevity. The golden jubilee souvenir of the Time and Talents Club, which has organised scores of Western classical performances since it was founded in 1934, lists such now-forgotten outfits as the Symphony Orchestra of Bombay (conducted by Francisco Casanovas in November 1953), the Bombay City Orchestra (conducted by Vere de Silva in February 1957), the Bombay Chamber Orchestra (under the baton of several musicians in the 1960s). As these polished recordings by Mehli Mehta and his Sextette demonstrate, these ensembles proved just how far amateurs can go if they put their minds to it.

5 comments

the Prelude is outstanding, moving!

Great article! Thanks…Mr.Scrinzi must have been the one who taught the basics of Western Music to Prof. B.R.Deodhar(who ran the legendary School of Indian Music near Opera House). I knew about Scrinzi through my readings on Indian Music, but this is whole new information gateway…Damn nice!

Kuldeep sir,

Indeed, the same Scrinzi. Just email you some articles he wrote on the relationship between the music of East and West…

I’m researching the connection between Indian and Western music, particularly in and around Bombay. I’d really appreciate any more information about or articles by Scrinzi.

Thanks so much

Hi Naresh,

Thank you for posting this article and I really enjoyed reading it. I’m just wondering if you had any links to photos or works by a Francisco Fernandes from Goa. He would have been in the Bombay symphony orchestra back in the 50’s or 60’s.

Thank you

Steve