[This is a slightly edited version of the Preface to Taj Mahal Foxtrot. It appears in the latest issue of Time Out Mumbai.]

Taj Mahal Foxtrot, a tale that unfolds across five continents, began mundanely enough with a stroll down the street to interview a musician who lived around the corner from my home in Bandra. It was 2002 and the objective of my mission, I must confess, wasn’t entirely noble. I was seeking to excavate gossip about a scandalous affair that had titillated the world of migrant Goan musicians in Mumbai in the 1960s. Being inherently lazy, I had decided to bring my inquiries as close to home as possible and made an appointment with the musician-father of my college friends Larissa and Max Fernand. I didn’t know much about the man, except that he’d played in jazz bands and in the Hindi film studios. He seemed as good a starting point as any other.

Though Larissa warned me that her father had Parkinson’s disease, I hadn’t realised just how tortuous it would be for Frank Fernand to carry on extended conversations. Each time I asked a question, he’d tense up, pull himself upright in his wheelchair for a moment and finally let four or five sentences fly. Then he’d sink back for a few minutes, catch his breath and we’d be off again.

If he was frustrated that his body couldn’t go where his mind wanted it to, he didn’t show it. I felt guilty about putting him through so much exertion but it was obvious that he had many stories that he wanted to tell – not only about the relationship between the Goan crooner Lorna and her band leader Chris Perry but also about the many musicians he’d performed with over a long career that had begun in 1936 and why he and his friends had come to love jazz so much.

If he was frustrated that his body couldn’t go where his mind wanted it to, he didn’t show it. I felt guilty about putting him through so much exertion but it was obvious that he had many stories that he wanted to tell – not only about the relationship between the Goan crooner Lorna and her band leader Chris Perry but also about the many musicians he’d performed with over a long career that had begun in 1936 and why he and his friends had come to love jazz so much.

It soon became apparent that I was speaking to one of the most important figures in India’s early jazz scene. Over the next few months, in spittley, staccato sentences, Fernand told me about a meeting with Mahatma Gandhi in 1946 that inspired him to try to play jazz in an Indian way and about his efforts to reinvent Goa’s Konkani folk music traditions. He also told me about itinerant African-American musicians who had come to Bombay in the 1930s and mentored India’s first jazz musicians.

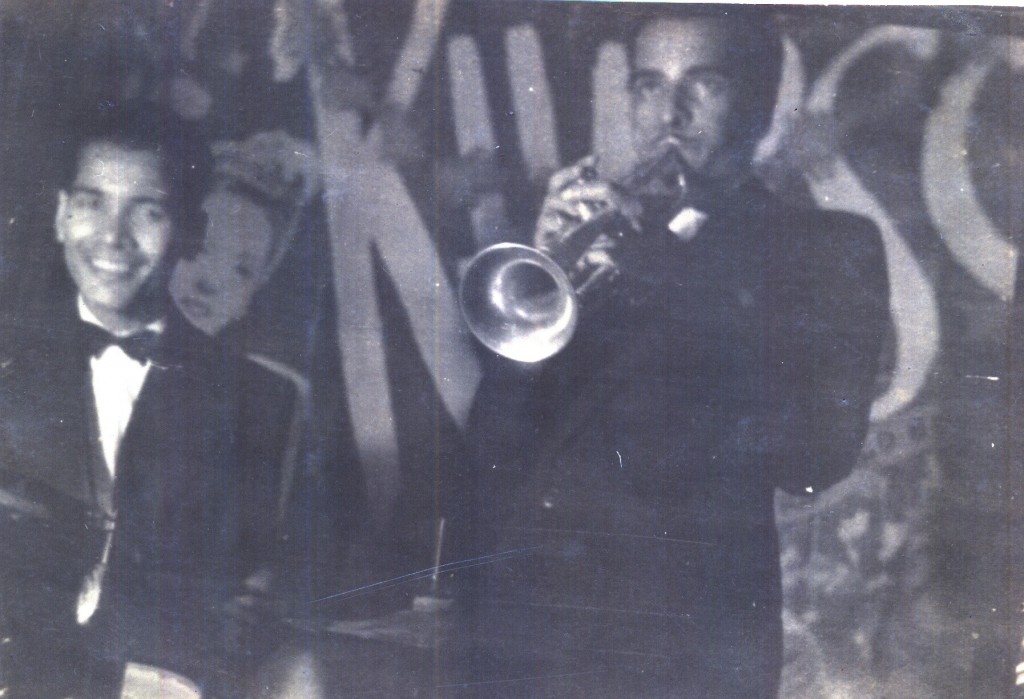

I almost didn’t realise the importance of the cultural exchange he had described. I didn’t recognise the names of the African-American jazzmen he mentioned and didn’t make much of them. But as my research progressed, I was fascinated to learn that the pianist Teddy Weatherford, who had hired Fernand to play with him at the Taj Mahal Hotel, had been Louis Armstrong’s band mate in Chicago in the 1920s before abandoning America for a career on the road in Asia. Another of Fernand’s mentors, the trumpet player Crickett Smith, had been featured on seminal recordings that captured the transformation of the rudimentary form of ragtime into sophisticated jazz. Before he came to India, Smith had spent long years in Europe, helping the French find their groove. When Fernand eventually told me about the role he and his Goan compatriots had played in introducing jazz into the Hindi film studios in the 1950s, the contours of the story became evident.

I almost didn’t realise the importance of the cultural exchange he had described. I didn’t recognise the names of the African-American jazzmen he mentioned and didn’t make much of them. But as my research progressed, I was fascinated to learn that the pianist Teddy Weatherford, who had hired Fernand to play with him at the Taj Mahal Hotel, had been Louis Armstrong’s band mate in Chicago in the 1920s before abandoning America for a career on the road in Asia. Another of Fernand’s mentors, the trumpet player Crickett Smith, had been featured on seminal recordings that captured the transformation of the rudimentary form of ragtime into sophisticated jazz. Before he came to India, Smith had spent long years in Europe, helping the French find their groove. When Fernand eventually told me about the role he and his Goan compatriots had played in introducing jazz into the Hindi film studios in the 1950s, the contours of the story became evident.

Full piece here.

1 comment

This pathbreaking book even helps explain how it took a Muslim sitarist/musicologist,

bred in Bombay, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy (1927-2009) to start the Jazz Program at UCLA as part of the newly created Ethnomusicology Department in 1988. This was after he spent years in the London jazz scene

in the 60’s as a pseudonymous sitarist (to preserve his dignity as a lecturer in Indian Music at SOAS) with the likes of Andy Sommers, Zoot Money, and others, i.e.:

Curried Jazz (LP). Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, composer and soloist, under pseudonym “Dev Kumar.” London: 1967.

Paul Hamlyn EMI Records, MFP 1307.

May TMF begin a Jazz Revival in Mumbai!

amy catlin-jairazbhoy, UCLA Ethnomusicology Department, Herb Alpert School of Music