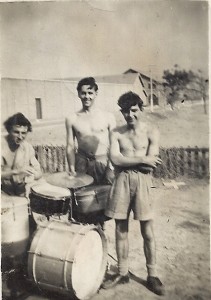

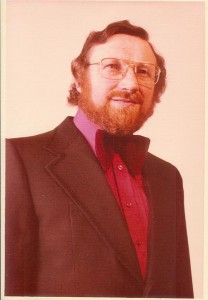

“I’m a ‘dance’ band drummer, always was, and always will be.” That’s what 87-year-old Roy Holliday declares on his Facebook page, and the way he’s playing the drums in that clip, it’s clear that he intends to keep beating the skins for a long time to come. Holliday lives in the UK and stumbled upon the Foxtrot website because he was trying to locate Indian jazz musicians he met in the hill station of Mussoorie in the summer of 1947, months before Partition. He’d come to India earlier that year as a member of the Royal Air Force.

He’s been kind enough to let me reproduce a section from his as-yet-unpublished memoir:

“India was a revelation, from the moment we landed the air was filled with exotic sights, sounds and smells. Our first two days in Bombay were spent aboard the ship as the transit camp at Worli was not ready to receive us. We were however allowed ashore to do some sight-seeing and I even managed to escape the heat in an air-conditioned cinema. But we were not prepared for the poverty and the sight of thousands of people sleeping in the streets.

“India was a revelation, from the moment we landed the air was filled with exotic sights, sounds and smells. Our first two days in Bombay were spent aboard the ship as the transit camp at Worli was not ready to receive us. We were however allowed ashore to do some sight-seeing and I even managed to escape the heat in an air-conditioned cinema. But we were not prepared for the poverty and the sight of thousands of people sleeping in the streets.

There were many other cultural changes for us and at our transit camp we became acquainted with the old colonial system which was still in operation at that time. We were allocated to billets each containing 16 beds, with two Indian servants or ‘bearers’ to clean our shoes and press our uniforms. The days here were spent in idleness, after a morning parade and breakfast we scanned the notice board to see if the daily orders contained details of our postings, and if your name did not appear, the day was yours to spend as you pleased. Many of us passed the day at Breach Candy, a swimming pool with a bar and waiters to bring ice-cold drinks to your reclining chair at the poolside.

There were some good restaurants and coffee houses in Bombay, where even impoverished airmen could afford to eat. There was also the wonderful Taj Mahal Hotel with a good band led by a gentleman who rejoiced in the name of ‘Chick Chocolate’. He and his band were India’s foremost exponents of jazz, mainly in the style of Louis Armstrong.

After almost three weeks this idyll came to an end, there it was on the notice board, my name with about four others. We were being posted to 107 M.U. Karachi, a 24-hour rail journey involving a least one change of train. A great shock awaited us on arrival as we were not expected for another week and no accommodation had been prepared for us, so we found ourselves living in rather small tents, with none of the creature comforts that we had come to expect. I celebrated my 21st birthday in one of those tents with two pals and several bottles of Indian beer.

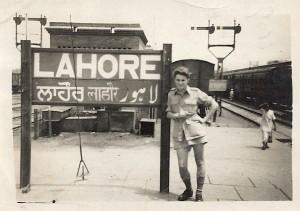

Eventually at the end of June 1947, three of us, a clarinettist, a trumpet player and myself, made our way to Karachi’s main railway station to begin our long journey to Mussoorie, a delightful place in the foothills of the Himalayas above Dehra Dun. We arrived at our destination to find a large beautiful bungalow set in the most wonderful flower-filled garden. The large building was encircled by some smaller bungalows set some short distance away, these were to be our lodgings for the next two weeks or so. This glorious place, which was as good as any first-class hotel, was in reality the Y.W.C.A. Because there was no Y.M.C.A. in Mussoorie, they took in men. We were not however allowed to sleep in the main building: that was reserved for the young and not-so-young ladies. We were relegated to the rather comfortable bungalows in the grounds.

Eventually at the end of June 1947, three of us, a clarinettist, a trumpet player and myself, made our way to Karachi’s main railway station to begin our long journey to Mussoorie, a delightful place in the foothills of the Himalayas above Dehra Dun. We arrived at our destination to find a large beautiful bungalow set in the most wonderful flower-filled garden. The large building was encircled by some smaller bungalows set some short distance away, these were to be our lodgings for the next two weeks or so. This glorious place, which was as good as any first-class hotel, was in reality the Y.W.C.A. Because there was no Y.M.C.A. in Mussoorie, they took in men. We were not however allowed to sleep in the main building: that was reserved for the young and not-so-young ladies. We were relegated to the rather comfortable bungalows in the grounds.

Immediately on arrival we were invited to take tea with the more senior residents and whilst they were most polite, they made it quite clear that we were to behave ourselves with the utmost decorum. Little did they know of our bottles of liquor hidden in our bungalows. India at that time had peculiar licensing laws which forbade the sale of liquor except for a couple of hours a day – that is, between four and six in the afternoon. Therefore if you were going to a restaurant in the evening, all your alcoholic beverages had to be ordered in the afternoon, on arrival your unopened bottle or bottles were waiting on your table, ostensibly purchased and paid for during the legal hours (shades of the London bottle parties).

Immediately on arrival we were invited to take tea with the more senior residents and whilst they were most polite, they made it quite clear that we were to behave ourselves with the utmost decorum. Little did they know of our bottles of liquor hidden in our bungalows. India at that time had peculiar licensing laws which forbade the sale of liquor except for a couple of hours a day – that is, between four and six in the afternoon. Therefore if you were going to a restaurant in the evening, all your alcoholic beverages had to be ordered in the afternoon, on arrival your unopened bottle or bottles were waiting on your table, ostensibly purchased and paid for during the legal hours (shades of the London bottle parties).

There were three restaurants of note in Mussoorie and we patronised them all. There was music in all three and in no time at all we had become friendly with the musicians in two of them. At Hackman’s restaurant, the band was lead by Rudy Cotton and it was made up of good-class musicians who liked to play a little jazz. On the second visit to the restaurant, we were invited to play, it became a nightly routine for us to sit in with the band. At the Standard, the band was lead by Sonny Lobo, who also favoured the music of the black American bands. The drummer in Sonny’s band went by the name of Claude Kenny [whose grandson Luke Kenny would become a popular VJ – nf] and he was rather good.

I asked him who had taught him and he replied, ‘The finest drummer in India.’ When I enquired who that might be, he replied, ‘Claude Kenny.’ After we became better acquainted with the boys in the band, we were invited to play for a whole evening so that the band could have a night off. This we did and we were rewarded with a fine meal and plenty of drinks.

I asked him who had taught him and he replied, ‘The finest drummer in India.’ When I enquired who that might be, he replied, ‘Claude Kenny.’ After we became better acquainted with the boys in the band, we were invited to play for a whole evening so that the band could have a night off. This we did and we were rewarded with a fine meal and plenty of drinks.

The name of the third restaurant was the Savoy. The band there was lead by a White Russian named George and it had a not-so-young lady playing piano and it featured violins and accordions, the kind of music that we, being well up in the latest vernacular, described as square. In later years several of the musicians, especially those in Rudy’s band, made their way to England.

As always all good things must come to an end and all too soon our two weeks were over and we reluctantly said good bye to the local musicians, our idyllic surroundings and some new found friends at the Y.W.C.A.

On our return to Karachi, preparations for that part of India to become Pakistan were in full swing. There was to be a big military parade in the  morning and a large garden party for the officers and civil dignitaries in the afternoon which would go on until the early hours of the following morning. The band from our station was heavily involved and acquitted itself well providing light music for the afternoon, then a small group of us played for the cocktail party attended by Earl Mountbatten. After some much needed refreshment, liquid and otherwise we went on to play for dancing ’til four in the morning. Within days of Partition, it was announced that British forces were to be withdrawn from what was now Pakistan and by the end of August we were told that we would be leaving in mid-September. We duly embarked on the SS Dunera and began our journey home.”

morning and a large garden party for the officers and civil dignitaries in the afternoon which would go on until the early hours of the following morning. The band from our station was heavily involved and acquitted itself well providing light music for the afternoon, then a small group of us played for the cocktail party attended by Earl Mountbatten. After some much needed refreshment, liquid and otherwise we went on to play for dancing ’til four in the morning. Within days of Partition, it was announced that British forces were to be withdrawn from what was now Pakistan and by the end of August we were told that we would be leaving in mid-September. We duly embarked on the SS Dunera and began our journey home.”

Follow Roy Holliday on Facebook here.

1 comment

Wow – Roy is a good friend of mine and taught me drums when I was a youngster back in the 80s. As the notes on this site say, he continues to play today, and thrills audiences and younger drummers with his extraordinary drumming. When we meet, he shares stories of his earlier playing days in India and life after in the UK; as a British Asian myself I am as fascinated by what he shares as by my own parents stories of their life in a colonial Anglo-Indian environment, and in the events of pre and post partition.

Roy’s experiences and his willingness to share them are treasures to me. What he shares as a musician and as a really kind, gentle and humane individual serve as inspiration.

Anyone reading this UK-side, try and get to see Roy play live if you can; and grab him for a chat after – you won’t regret it!