The blues, as fans well know, come from a place of pain, but few performers have to face hazards like these on the way to a concert: “Sweltering heat, fever, wild tigers, Jap snipers, leeches and other insects that latch onto the skin so tight, the only way they can be removed is by burning them off.” Sometimes, she’d have to step over decaying bodies and there was always the prospect of bomb raids.

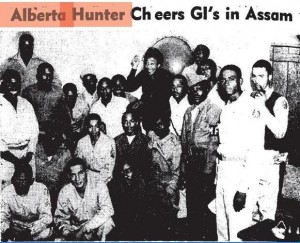

These were the circumstances in which Alberta Hunter belted out the blues in Assam in 1944, as she attempted to cheer up US troops building the snaking Ledo Road in the C-B-I region between China, Burma and India.

These were the circumstances in which Alberta Hunter belted out the blues in Assam in 1944, as she attempted to cheer up US troops building the snaking Ledo Road in the C-B-I region between China, Burma and India.

By the same she died at the age of 89 in 1984, Alberta Hunter was a genuine legend – an elegant granny who would sing bawdy blues tunes with the poise of a minister leading a church choir. She’d toured Europe in 1917, started recording prolifically in the 1920s, and in 1928, performed with the great Paul Robeson in the London version of Showboat. So it isn’t surprising that she caused a storm in Assam, when she showed up with a troupe of musicians in the middle of the Second World War to entertain the African-American soldiers who were constructing a snaking road in the jungle from north-eastern India to Kunming in China.

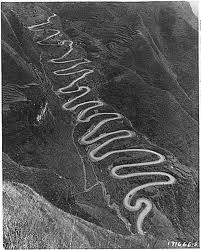

The Allies began to work on the Ledo Road (later renamed the Stilwell Road after the American general in charge of the operation) in 1942. It would eventually become a 769 km highway, but the construction in the mountainous terrain was arduous. Perhaps not coincidently, 60 per cent of the 15,000 US troops assigned to the task were African-American. They worked alongside 35,000 Indian and Burmese labourers. Approximately 1,100 Americans are thought to have died during the operation. Though there are no firm estimates, even larger numbers of Indians and Burmese are thought to have perished building the road. The cost of the project was estimated at $150 million.

The Allies began to work on the Ledo Road (later renamed the Stilwell Road after the American general in charge of the operation) in 1942. It would eventually become a 769 km highway, but the construction in the mountainous terrain was arduous. Perhaps not coincidently, 60 per cent of the 15,000 US troops assigned to the task were African-American. They worked alongside 35,000 Indian and Burmese labourers. Approximately 1,100 Americans are thought to have died during the operation. Though there are no firm estimates, even larger numbers of Indians and Burmese are thought to have perished building the road. The cost of the project was estimated at $150 million.

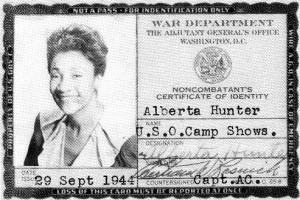

It was clear that everybody needed a little morale-boosting, so in August 1944, Alberta Hunter signed up with the United Service Organisations, which worked with the US defence department to provide entertainment to the troops. She was put in charge of Unit 342, which included a trio from Chicago called the Rhythm Rascals, a dancer and a trumpet player. The group left New York on October 15, 1944, and arrived in Calcutta after stopovers in Casablanca, Cairo and Karachi. Hunter’s tour of duty is described in vivid detail in Alberta Hunter: A Celebration In Blues by Frank C Taylor and Gerald Cook, and also in African-American papers like the Chicago Defender and the Afro-American.

With Calcutta as a base, the musicians travelled to military sites across the region, in trains and planes and trucks. Each member wore a jacket with a US flag on the back. When the group arrived at the impromptu stages that had been built in forest clearings, the excitement was palpable. “The soldiers would scream so loud you could hear them from here to Berlin,” Hunter recalled. The grand dame would walk out on to stage snapping her fingers and commanding attention. As another member of the group recalled, “Alberta would sign a song like, If I Could Be With You and have the men hollering. Then she would holler back at them, ‘Suffer, you dogs’, and they would take it in great fun.”

With Calcutta as a base, the musicians travelled to military sites across the region, in trains and planes and trucks. Each member wore a jacket with a US flag on the back. When the group arrived at the impromptu stages that had been built in forest clearings, the excitement was palpable. “The soldiers would scream so loud you could hear them from here to Berlin,” Hunter recalled. The grand dame would walk out on to stage snapping her fingers and commanding attention. As another member of the group recalled, “Alberta would sign a song like, If I Could Be With You and have the men hollering. Then she would holler back at them, ‘Suffer, you dogs’, and they would take it in great fun.”

At the end of 1944, she sent the readers of the Chicago Defender a letter datelined “Somewhere In India”. “Just a quick note from one of the most picturesque countries in the world,” she said. “We are the first USO show to play in this theatre and they are receiving us with open arms.”

Here’s what the newspaper Slip Stream had to say about her performance on February, 1945, in Agra: “She was worth waiting for as she cajoled, ‘Talk to me boys.’ For thirty minutes, she sang, stuttered and talked as GIs tore up the benches and yelled for more. Her final number, Basin Street, had every man in the Bowl hanging limply on the ropes as the show closed.”

In between the shows, the musicians chatted with the solders, served them doughnuts and helped them write letters home. When she gave interviews to the US press, she made certain to mention the names of as many soldiers as she could , keen to let their families know that they were alive. “You will never know how much a letter means until you are where it takes mail a long time to reach, so impress it upon everyone to keep the letters coming,” she told readers of the Afro-American in March, 1945.

Though USO entertainers carried the rank of captain, racist officers sometimes didn’t allow them to eat in the mess for senior staff. On such occasions, Hunter would refuse her meals, though the others, famished from the work, would usually eat in kitchen after complaining.

Though USO entertainers carried the rank of captain, racist officers sometimes didn’t allow them to eat in the mess for senior staff. On such occasions, Hunter would refuse her meals, though the others, famished from the work, would usually eat in kitchen after complaining.

Like the men they were entertaining, the musicians sometimes had to face barrages of shells and would have to duck in foxholes to avoid danger. “Despite performing under the most hazardous conditions…I tell you the pleasant smiles that came over the faces of the boys is enough for me,” Hunter said. “Even when a wild tiger jumped into the tent of our troupe and mauled one of our performers, this did not stop us from filling the bookings.”

Alberta Hunter wrapped up her India tour at the end of March, 1945, taking home her metal meal tray and her denim jacket as a souvenir. A few months later, she and the group were invited to Germany by General Eisenhower himself to play at a reception for his allies, the British commander Bernard Montgomery and Soviet Field Marshal Georgi Zukhov. According to the Afro-American, “Marshal Zukhov and Gen Montgomery beat rhythmic tattoos and swayed with the syncopators, showing that they enjoyed every minute of the entertainment. Gen Eisenhower would not let the entertainers leave”, so they had to cancel their next show and spend the night in the neighbourhood.

In 1954, Alberta Hunter effected a radical career switch. She became a nurse, and worked in hospitals until she was eased into retirement in 1978. But bored with the inactivity, she accepted an offer by a club in Greenwich Village to start performing again that year and, in her 80s, she was back on stage, making recordings and touring the world. Here’s a link to some of her earliest recordings and below is a clip from a concert in 1982, a couple of years before her death.

4 comments

Great article and much respect to Alberta.

what a story! you continue to amaze, Naresh.

Amazing story. Many thanks.

Thank you so much, Naresh