This isn’t about Bombay jazz but I decided to make an exception since it’s broadly about Bombay musical culture. Here’s the text of remarks I made at the launch of Ajay Bose’s book Across the Universe at the Opera House in Bombay in March 2018.

In my neighbourhood of Bandra, they still tell the story of a young man who was sitting on a wall in the 1960s, playing My Sweet Lord, when a scraggly hippy with a guitar on his back stopped to listen. As the Bandra boy finished the tune, the hippy is supposed to have exclaimed: “You play that song even better than I do. My name is George Harrison.” And as a sign of his approval, Harrison is said to have taken the guitar off his back and given it to the chap as a gift .

As I was reading Ajoy Bose’s fascinating book about the Beatles in India, I decided I should play my parochial part by doing a little research on the Beatles in Bandra.

Of course, many stories about the Beatles in Bombay are already pretty well known. A few years ago, I participated in BBC radio programme by the writer Safraz Mansoor called Bombay’s Beatle. The show revolved around the time in 1968 when George Harrison came to the city to record the soundtrack to a film called Wonderwall, which featured Indian classical musicians like tabla player Mahapurush Misra, surhbahar player Chandra Shekhar and santoor maestro Shivkumar Sharma.

We walked down Pherozeshah Mehta Road to peer at the fading sign of the HMV studio where the sessions had taken place and Sarfraz interviewed some of these musicians about their time in the studio with Harrison.

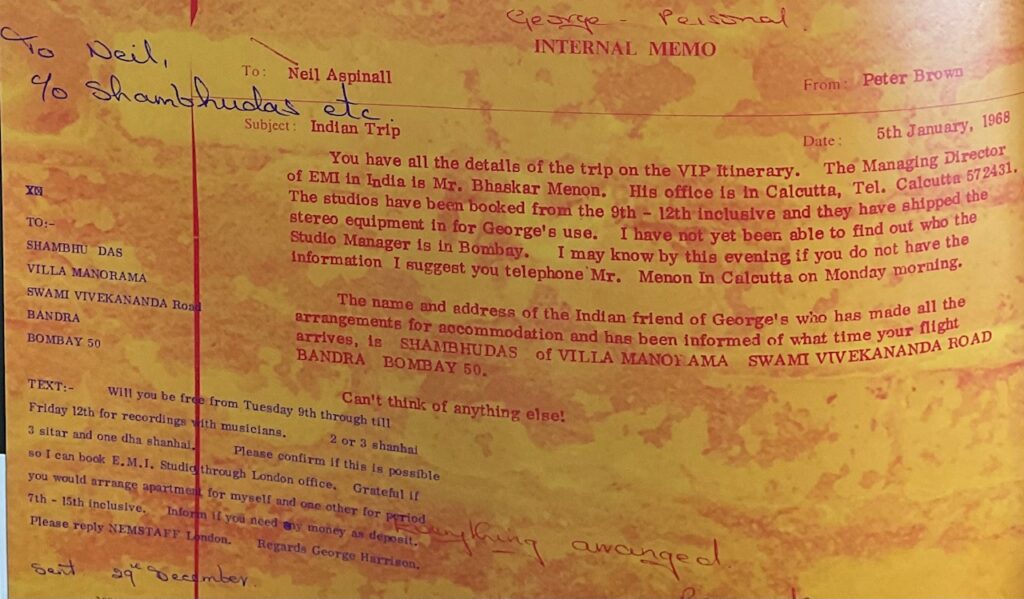

Years ago, when I bought that enormous book of pictures and photographs and other memorabilia called The Beatles Anthology, I had been delighted to find, on page 280, the image of memo that had been sent to Neil Aspinall, the band’s manager, from HMV’s India office, about the trip Harrison was planning to make to Bombay in January, 1968. It refers to one of Ravi Shankar’s senior students, Shambudas.

“You have all the details of the trip on the VIP itinerary,” the memo said. “The studios have been booked from 9th-12th inclusive and they have shipped the stereo equipment in for George’s use. The name and address of the Indian friend of George’s who has made all the arrangements for accommodation and has been informed of what time your flight arrives is Shambudas of Villa Manorama, Swami Vivekananda Road, Bandra, Bombay 50.”

Since reading this, I’ve been looking out for Villa Manorama each time I walk down SV Road, but I haven’t yet spotted it. So to try to piece together the story of Bandra’s Beatle, I thought it would be a good idea to try and track down the chap to whom Harrison gifted his guitar.

I first heard the story from a guitar player named Charlie Britt, whose brother, for reasons that are now shrouded in the mists of time, was known in Bandra as Harry Bonda. Charlie had been a longtime member of a beat group called the Crimson Rage. When I went to see him a few days ago, Charlie told me that his mother was sure she had seen George Harrison walking down Pali Hill Road several times. And he confirmed bits of the story about the chap on the wall. Only, it turned out that he wasn’t from Bandra, after all. He was from Santa Cruz and his name was Glen Lopes.

Charlie warned me that Glen had become a recluse, so it would perhaps be difficult to get him to talk. When I finally got Glen on the phone, it transpired that Charlie was partially right. Glen told me firmly but politely that he couldn’t meet me in person and that he was wary about talking on the phone because his line was tapped. He said he’d never spoken to any journalists about this episode. And then he proceeded to chat with me for 20 minutes. There was no wall involved and no scraggly hippie wandering by. As it turns out, Glen was introduced to Harrison by a mutual friend – he wouldn’t say who – and spent several evenings jamming with Harrison at the friend’s home – and of course, he wouldn’t tell me where exactly this was.

The first time they met, Glen said, he decided to play a Brazilian tune. Harrison laughed and asked, Brazilian? For a man who was trying to discover the very soul of India, it seemed odd to find Indians who could play all the bossa nova classics, and sing in perfect Portuguese. Of course, Harrison didn’t think it was odd that a long-haired fellow from Liverpool was trying to play the sitar.

Those jam sessions proceeded for several evenings. Among those who was also there was Dilip Naik, the fabulous Bollywood sessions guitar player. Evidently, these jams were recorded, but Glen isn’t sure who has the tapes. Glen told me that Harrison had a few meetings with Kersi Lord, the multi-instrumentalist who was a rising star in the world of Bollywood music, at his home opposite Almeida Park in Bandra – and so it’s entirely plausible that Charlie’s mum saw him walk by.

One day, shortly after Harrison had returned to England, Glen was told that he’d left a guitar behind for him. It wasn’t a gift, evidently, as much as a loan – Glen was told that Harrison didn’t want to keep carting the instrument back and forth across the continents, so he should hold on to it until Harrison returned to India. As it turned out, Harrison never came back to reclaim that guitar.

Last night, I decided to see if any of this information could be corroborated by sources online. There was absolutely nothing about it. But to my delight, I discovered that there was a second Harrison guitar in the suburbs. It’s prominently displayed on the wall of a restaurant called Café Gostana. And Arpana Gvalani, who owns the place, told me the charming story about how it got there. Evidently, Harrison had stayed at a hotel on Pali Hill called Oscar, which is now called Le Sutra, I think. Opposite it is Padamsee Apartments. When Ismail Padamsee of Padamsee Apartments heard that Harrison was in the neighbourhood, he invited him for tea. Harrison so enjoyed himself, he visited them again several times and when he was leaving, he gave Padamsee one of his guitars, a Gibson, made in Japan.

Years later, when Padamsee’s grandson Khalif Mitha realised that his friend Arpana was a huge Beatlemaniac, he passed it on to her. So if you’re up to it, you can go down to Arpana’s café, get photographed with the instrument and eat a special seven-pulse vegetarian burger she’s created. You need to tell the waiter you want a George.

Listening to Arpana and Glen tell me their stories and reading Ajoy’s book this past fortnight reminded me yet again of the incredible power of the songs that the Beatles created. Their tunes are so captivating, they’ve left each of us with the conviction that we have individual connections with those four musicians, even if we don’t possess a physical artefact that they’d once owned. They’ve touched the lives of people around the world in unimaginable ways, some seemingly tiny, others rather more cosmic.

For one Sindhi couple on the street next to mine, a Beatles song made them decide to name their baby Michelle. Others have been inspired to get tickets to ride on Magical Mystery Tours, to come to the understanding that all you need is love, to follow the sun. And as the world changes and we come to the realisation that all things must pass, the magic of the 300 or so tunes recorded by the Beatles remains the one thing we can rely on. As they pointed out, all you got to do is twist and shout.

The Harrison Archive has more images and recollections about those sessions. Click here.