Portrait of Prahlad Mehta by Hal Green (Extract from the manuscript books)

By Nakul P. Mehta

Saxophonist Nakul Mehta, who has a storehouse of memories about the Indian jazz scene, has generously donated a stash of manuscript books belonging to Hal Green to the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology in Gurgaon. Here’s a note he wrote to put them into context.

Hal Green was a woodwinds, guitar and violin player who performed in, and led, a number of jazz groups in Bombay from the 1930s onwards.

Before they joined the Weatherford band, Hal Green and his younger brother Henry had led the eight-member Elite Aces at the Taj in 1933, performing what Ali Rajabally [who wrote a series of unpublished articles about India’s early jazz scene] described as dance music with a jazz accent. Hal Green played guitar, reeds and the violin, while Henry was a bassist and saxophonist.

“The type of music they had brought with them may be an overworked cliché today but it was an unheard-of departure then,” Rajabally wrote. “Night after night, Hal and his alto sax drove the band through performances so exultantly searing that no band in the country, local or foreign, could have successfully challenged them for the No. 1 spot.”

My father, Prahlad C Mehta (1927-1991) developed a life-long love of jazz music in his late teens after hearing a recording of the Benny Goodman Quartet (with Teddy Wilson on piano, Gene Krupa on drums and Lionel Hampton on vibraphone) play Whispering on All India Radio. He recalled regularly listening to Ken Mac’s band at the Willingdon Sports Club on Saturday evenings in sessions that featured Sollo Jacobs, Hal and Henry Green, Norman Mobsby and others.

In the late 1940s, he began piano lessons with Francis Saldanha and, soon thereafter, weekly clarinet lessons (for a fee of Rs 5 per session) with Hal Green. When his older brother brought him a Buescher alto saxophone from the US in 1948, he switched instruments, still under the tutelage of Hal Green.

He occasionally took part in the regular jam sessions that were held for jazz enthusiasts at a warehouse on Reay Road in Bombay, along with regulars like Rustom Captain (piano), Dhun Nasikwala (drums) and Noshir Sethna (clarinet).

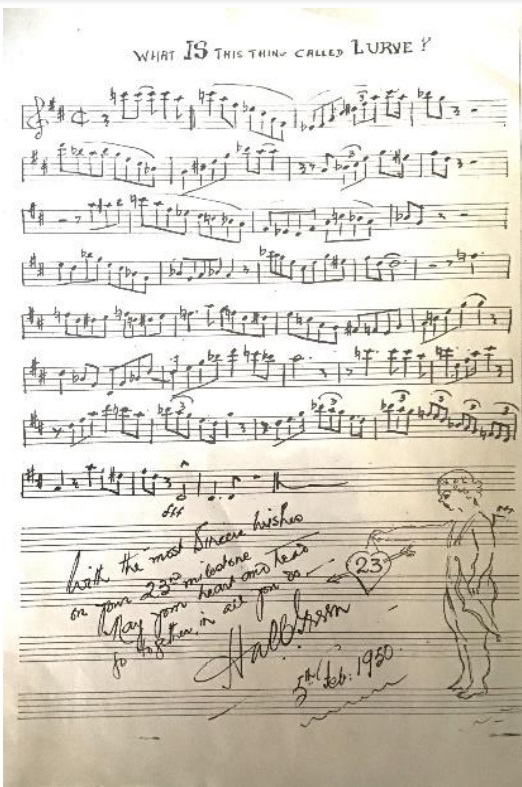

These manuscript books, written by Hal during this time, cover the arc of an education in music. They begin with the instrument’s finger-board; then notation, scales, chords and harmony; moving on to jazz etudes, tone poems, and duets; and finally, to solos of remarkable sophistication on jazz standards. My father recalls that these were improvised on the spot and written extempore, as Hal, pen in hand, hummed the phrases and notated them on the fly. All of Me and What Is This Thing Called Love were two of my father’s favourite songs at the time, and there are several solos written for both, along with popular jazz standards of the period.

Solo written by Hal Green on the chord changes of What is This Thing Called Love on the occasion of Prahlad Mehta’s 23rd birthday in 1950. (Extract from the manuscript books)

Hal was often compared with the tenor saxophonist Norman Mobsby; inevitably, as they were perhaps the two most innovative saxophone players in Bombay at the time. Mobsby was said to be the more lyrical in his phrasing, while Green was edgier and more experimental. This is apparent in Hal’s written solos in these books; he seems at ease both with a swing sensibility and with bop phrasing.

As work pressures grew, my father stopped playing the saxophone in the mid-1950s. Hal Green emigrated to the UK, probably around this time.

In 1992, I fortuitously met Francis Saldanha, who was playing solo piano at a bar at a hotel in Juhu, in Bombay. Our introductory conversation seemed to convince him of my jazz credentials and, once we had connected the dots, soon led to his telling me about my father having been his student.

Several of these manuscript books had somehow come into his possession and, over a series of reminiscent meetings at his apartment in Santa Cruz in Bombay, he insisted on returning them to me.

At the time I also told Francis that I was keen to learn the saxophone. He promptly put me in touch with Micky Correa, the legendary band-leader and multi-instrumentalist, with whom I studied for six years; thus began a very rewarding phase in my life that culminated in my becoming a performing musician. Hal Green’s manuscript books, and their trajectory of basics to a challenging level of technical and harmonic skill, proved an invaluable learning resource.

I met Hal Green only once, in London in 1975, but these documents that I inherited speak volumes about his personality. The music aside, they contain quirky remarks, whimsical instructions, and sketches that demonstrate the keen eye of an artist.

The eminent jurist Soli Sorabjee is also reported to have taken clarinet lessons from Hal Green. Read about it here.

Hal Green and his Elite Aces.