On January 18, Badal Roy’s niece, Piali Roy, announced that the pioneering tabla player had passed away. Here’s a piece I wrote about him in 1998.

Brandishing his spatula like a conductor’s baton, Badal Roy served up a plate of sizzling mutton kababs one recent New York afternoon. As the aroma of the spices filled the dining room of the jazz world’s most famous tabla player, he reeled off the recipe: coriander leaves, capsicum, chili powder. But the tangy edge, Roy revealed, came from a special ingredient he called “khajoon”.

Khajoon?

“This stuff,” he said, reaching into his kitchen cabinet and pulling out a jar of lurid yellow Cajun, the fiery powder that residents of the southern US state of Lousiana refer to as “kay-jin”.

In his music, as in his cooking, the 53-year-old Roy has melded cultures, leaving jazz with the tantalising taste of Indian funk. His fascinating rhythms have seasoned the albums of some of jazz’s boldest innovators. For the last ten years, Roy has been part of saxophone genius Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time ensemble. He toured for three years with trumpet legend Miles Davis. Among the others with whom he has gigged or recorded: hornman Dizzy Gillespie, reedman Pharoh Sanders, guitarist John McLaughlin and flute player Herbie Mann.

“Badal Roy and his tablas have added a new rhythmic dimension to jazz,” says Robert Browning of the New York-based World Music Institute. “He’s among the most important figures in the Indo-jazz crossover.”

Adds fellow Ornette Coleman sideman, the guitarist Kenny Wessel, “Badal’s tablas are full and orchestral and colourful. His music is joyful and his joy is immensely infectious.”

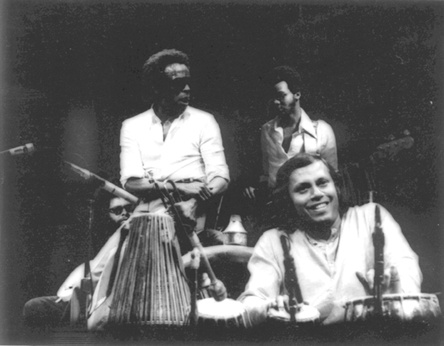

That contagion was obvious when Roy and Wessel – who perform as a trio with Japanese bassist Stomu Takeishi – strutted their stuff in March at New York’s hip Knitting Factory. Surrounded by eight tablas and bathed in a purple glow, Roy dug out a groove that had the audience bouncing in the seats. Heads began to nod manically as the man in the black kurta picked out a plaint pattern using puja cymbals. And as he began to scat, smiles swept through the room faster than an East Asian currency depreciating.

For Roy, the smiles are the best form of appreciation a musician can be shown. “You play a couple of notes, you make a couple of people happy, you’ve done your job,” he says.

It’s a job Roy never thought he’d be doing. When he came to the U.S. in 1968 to do a doctorate at New York University, he expected eventually to make his living as a statistician. Music was only a hobby. Roy never studied the tabla formally, something he believes has worked to his advantage. ” I wasn’t bookish. I was always open to new sounds,” hesays. “Too many classically trained musicians refuse to go beyond the rules of their traditions.”

Roy’s metamorphosis from number cruncher to ace jazzman was dramatic . When his meagre savings ran out, Roy found work washing dishes in an Indian restaurant. He took to supplementing his income with a second job, performing with a sitar player. “Every night, this white guitar player would come and listen to us,” recalls Roy. “Then in the break, he’d ask to jam with me.”

After a few months of this perfunctory interaction, the musician – who Roy only knew as John – asked him to sit in on a recording session. The guitarist turned out to be Miles Davis sideman John McLaughlin and the recording session yielded the highly acclaimed My Goals Beyond album. Soon after, McLaughlin’s boss, Davis, hired Roy for a session.

“I was really nervous and I asked Miles what he wanted me to play,” Roy recalls.

Davis’s instructions were brief. “Play it like a nigger,” he told the young percussionist. “Play it from the heart.”

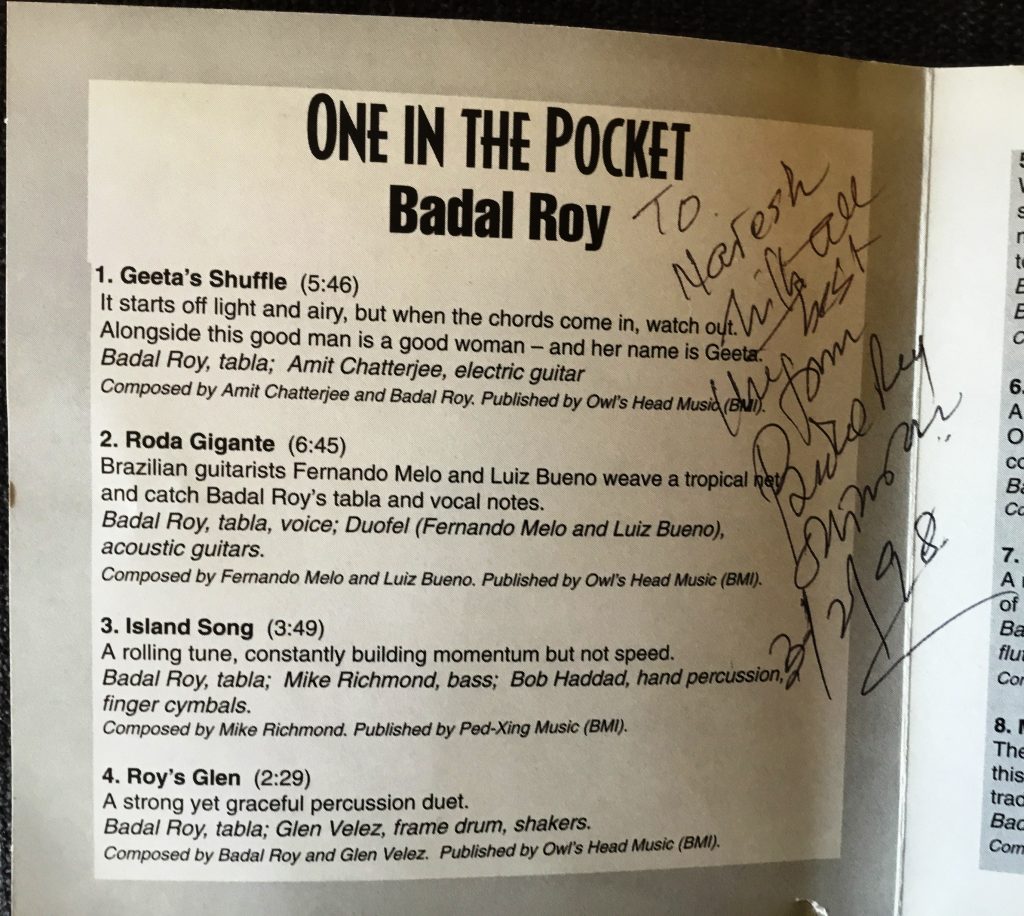

More than satisfied with Roy’s work on the On The Corner album, Davis asked him to tour with his band. And for three years, Roy found that his life was all shrimp cocktails and limosines. Since those flamboyant times, he’s earned himself reputation as an inspired percussionist, bringing “a bountiful spirit and an elastic musicality to the situations he plays in”, as Downbeat magazine recently put it. After working as a sideman on more than 50 albums, Roy headlined his own record called One In The Pocket late last year. It’s been strongly received by the critics.

That, says Roy, is enough to keep him content. “My music hasn’t made me a lot of money, it hasn’t got me five Mercedes Benzes,” he says. “But my name is listed in most jazz textbooks. What more could I want?”

1 comment

Dear Naresh,

I met you in Goa in 2018. I have been friends with Darryl since 1970!

My wife Antusa is from Malara, Diwar, Goa!

Maybe you will recall me